PodCastle 924: Reverent

Show Notes

Rated PG-13

Reverent

by Leah Ning

It’s the smell of gravity that tells me Father’s been to my rooms: empty and metal-sweet, the way you’d think a black hole would smell before it crushed your nasal cavities. Out here in the spire’s lowest hallway, it’s faint, hanging in the dark humidity of my hour like dust in a years-dead room. But I know it’ll thicken as I walk, weighting my lungs, and I know what I’ll find laid on my pillow and who Father wants it used for. I’ve seen this before. I’ve done this before. I’ve been dreading doing this again.

Someone will do this to me one day. At least it won’t be Noon.

I breathe the humid heat of the hour that follows mine and go to my door. My soft shoes hush against the pale cream floor. The door’s brass hinges creak when I open it. I suppose I should get someone to spin them back to new, but I’ve come to like the noise. It’s what wakes me when Noon comes in, her hour done and woven into the next.

Noon’s gotten worse lately. Losing time. Forgetting when she is. Hinges rust because time touches them, so they can be spun back, time’s fingerprints lifted from their slim barrels. We degrade because we are the ones who create those fingers, spinning them like yarn from the well of time in our core.

Our wells are finite. Our bodies are only finite when faced with the curved knife that lies sharp on my pillow.

I shut the door behind me and cross the room, my chest heavy with grief and that metal-sweet scent Father leaves behind. If I didn’t know who the knife was meant for by my love, I’d know it when my fingers brushed the blade. The knife is warm against my palm as if from long hours in the sun, smells of dry dead heat, burning sand, lake-wet skin.

We stand at opposite ends of the clock, opposite ends of the spire, so in the toothsome dark that follows my hour, Noon will still be asleep. I have options.

What I could do, if I chose to: climb to the top of the spire, silently open her door — whose hinges I won’t let degrade the way mine have — and cut her throat before she wakes.

What I should do: bring the knife to her rooms, wake her, take her in my arms, and let her choose where the knife goes.

What I do instead: stash the knife in a drawer beneath the silken blacks I wear to weave the smooth dark of my hour, climb to the top of the spire without changing out of today’s clothes, let Noon take them from me instead with her hands warm like summer blue. And after, as she dozes, her breath warm on my collarbone, I think of how I’m supposed to tell her. How I’m supposed to still that breath that would carry me down into sleep on any other night but this.

The first hour I fell in love with was Four, and she was nearing her end. I was still new, freshly ascended to Midnight, drawn to Four’s heavy deep-morning dark like eyelids gravid with sleep. She taught me to conserve my time, to spin tapestries as thin as vellum paper and tie them fast to the hours I lie between.

It’s an honor to hold Father’s knife. A relief to feel its bite, or so Four told me.

I brought it to her when I found it on my pillow, knowing what it was for, knowing it felt like her hour at winter freeze, like the soft skin of her waist against my fingertips. I brought it as a question, and she received it like an answer. Told me she wanted to go before she lost too much, and Father knew it. We have all seen the timeless things we might become if no hand brings that knife to us. Seven frozen deities we’re too afraid to touch, like they’re a contagion that could shut us outside time alongside them.

We fear that total loss more than we fear the unknown that lies beyond the knife. So Four thanked Father for the mercy while she took my hands, then thanked me for mine while she guided the blade into her own heart.

Noon wakes slow and luxuriant at dawn, her skin a blaze of golden pale even in that hesitant light. I didn’t sleep. I thought, and I watched the sky lighten through the glass of her walls, waiting for her breath to come conscious, her legs to stretch so I could run my fingers down the curve of her side.

She takes in a deep lungful of air, lets out a thoughtful hum, and says, “You don’t smell right.”

I nod. “I know.”

Her chest stalls halfway through her next questioning breath. “Father.”

I nod again.

Noon’s body goes still. The knife has never seemed like mercy to her. It makes her feel like prey. I don’t move, not even to tighten a comforting arm around her shoulders. If she wants to pull away, I’ll let her. If she wants to get up and run, I’ll let her. I might even help her.

She doesn’t move. That she trusts me this far is a light warmth in my chest, summer sun in the moonlit dark.

“I have an idea,” I say.

“Okay.” Her voice is cautious, her muscles still tense.

“I’m going to move.”

“Okay.”

I could tell her the knife is downstairs. I doubt she’d believe me. Or feel better even if she did.

I untangle myself from her, sweat damp where our skin parts, and sit up. The pale gold of her sheets pools in my lap. She stays where she is, curled on herself, her eyes clear denim blue on mine. Like if she stays still enough she could change my mind. As if it ever needed changing. As if I ever considered using the knife without her consent.

Four — the Four from back then — taught me well. When I dip into the well of my time, I don’t have to scrape. I find the humid black of summer midnight easy, pulling it up with my fore and middle fingers, spinning it to keep the syrupy texture from falling, breaking it off where it thins. Noon watches with a light crease between her brows.

“Sit up with me,” I say gently. “Please.”

She does, and the cumulus of her hair tumbles across her bare chest, her lips parted. I bring my fingers closer to her.

“Open,” I whisper.

I poke my fingers into her open mouth, and as she swallows the time I give her, she shivers, as if swimming into a cold pocket in a river.

Noon came to me not long after she ascended, her predecessor killed by Sixteen, and at first I thought it meant my time was coming soon. But noons have always been the exuberant ones, bright with sunshine at the sky’s peak, using their time with the thoughtless ease of the unknowing. I know how it looks to lose your when, even if, like Noon, it was only in flickers yet. I’ve loved Four and Nineteen and Eight, but I’ve seen noons come and go, and I’ve found them hard to love.

But this one. Oh, this one.

My Four told me that one of the hardest mercies Father gives is our loves. We fall knowing it will end with the knife in one hand and its blade buried in the other’s breast. We fall knowing we’ll end with someone we trust, knowing it’ll sweeten our last breaths, hoping it’ll gentle the bleeding.

But I fell hard for my Noon. If loving my Four was a swoon, loving Noon is tumbling from the spire’s peak, and I am still floundering through the wet of the clouds, unable to see the ground below.

There are different sorts of noon: the cold brilliance of winter sun, the thundering pale of spring storms, the unrelenting blaze that makes cicadas scream through summer. This one burns fast and meteor-bright, and when she first spent the night in my bed, I caught the first sign of her well of time dwindling to dry: a moment, before she dropped off to sleep, when she startled to wakefulness, caught her breath.

It took her weeks to admit that her when slips back to her birth sometimes, when Father forged her, stumbling with newfound legs from the fabric of the universe to watch, to learn, to wait until the current Noon used herself up and this new one ascended.

She never had to admit her fear of the knife. Her reluctance to speak of her failing grasp on time was admission enough. But that fear was never enough to stop her burning like the blinding white flash of magnesium, and I think that was the part that made me love her.

The time I give to Noon works.

She ate it from my fingers like honey and I spent the rest of the day watching her, counting her losses. I know them all by heart: the stutter of her steps when she crosses a threshold, the upward jerk of her chin at faint, bright peals of laughter, the hand that drifts to her ribs at the sound of a whisper, her fingers landing just where mine would.

But with my time added to her well, she no longer freezes at the scent of sandalwood, the perfume of the Fourteen she loved shortly before she came to me.

She no longer hums old songs at the touch of soft cotton.

I miss that one a little. I like her voice.

I would feel better about this if she didn’t startle herself awake when she dropped close to sleep beside me, lazing in the dusty heat of Thirteen’s hour.

I would feel better about this if I couldn’t still feel Father’s knife, warm and blood-hungry beneath my silks as I dress once more for midnight.

But for the first time, I do not consider the finite quality of my own well.

I meet Father for the second time three days after I found the knife.

We all meet Father once: on the day of our forging, when he makes us from matter and fills our wells with time the way you might blow glass. And when that task is done, he delivers us to the waiting hands of the twenty-four hours and twenty-three other hours-in-waiting of the spire.

Some of us speculate we meet him again the day the knife spills our blood, and he draws us out of time. None of us knows. We never see him in the spire, only know he’s visited by the occasional weighty scent of gravity, the blades left silent on clean white pillows. Some of us suspect he makes a knife fresh for each of us, weaves our magic to metal so it’ll consent to take lives that could, in our unchanging bodies, be infinite. Others suspect there’s only one knife, heavy with the blood of all the hours that came before.

I don’t know if I’m the only one to ever meet Father twice. I’m certainly the only one alive.

He sits on the edge of my bed when I come in, the hour handed over to One and Two, and he is not how I remember him. When I was forged, he was old, bald and bearded, starlight making gleaming points in the dark of his skin. He’s younger now, clean-shaven and with curls cropped close to the scalp. A smile touches his full mouth at my scrutiny.

“Time does as it likes with me,” he says. He runs the pad of one thumb over the knife in his hand. “Come sit.”

I give the knife another pointed glance and don’t move. I don’t know what he does to hours who refuse to kill their lovers.

“No,” Father says. “This is yours. I won’t have murder in this place.”

I still don’t move. “Tell me what you think murder is.”

“Here? If someone dies afraid and unconsenting, it’s murder.”

“Then you understand that what you want me to do to Noon is murder.”

He nods, his mouth twisted aside, gaze averted. “She’s not the first to be afraid. Nor are you the first to try what you have.”

Of course he knows. Time, for all I know, could be a window he peers through, each moment a place he can step into as he pleases.

“Why are you here, then?” I ask.

“To help before it’s too late for her,” Father says. “And for you. She burns just as fast now, but with your time instead of hers. It’ll go wrong soon. And then you’ll both run out.”

“What am I supposed to do?” I ask. “She’s afraid. She doesn’t know what happens to her when she dies.”

He smiles again. “Find what she needs to assuage her fear. Help her be unafraid. You’re drawn to her because you can do that for her.”

I cross my arms, silk cool against my skin. “Be unafraid of what? I don’t know any more than she does.”

“I don’t know either.” That smile lingers on his face still. “And I’ve never feared what isn’t in my path. But you feel that fear and know how to tame it.”

I shake my head. “I’ve used that knife enough not to fear it. I don’t understand her well enough to help.”

Father tilts his head. “Don’t you, though? You, who’ve spent all your moments counting each weave, thinning it as much as you can so you might have an extra few seconds?”

That puts a cold weight in my stomach that I don’t understand. It reminds me of Nineteen, how I put the knife through her heart and she told me it felt cold.

Maybe this is how it feels to be pierced, even only with a gaze. Cold, weighty, draining. I don’t like it.

“That isn’t why I do it,” I say anyway.

“Then why?” Father asks.

“Why did Four do it? My Four. The one who used my hands to take the knife to her own heart.”

He stays quiet, assessing. I notice for the first time, in the dark, that his eyes are voids of slick, endless black, empty like the space between celestial bodies.

“I don’t know,” he says. “Do you?”

“Wanting to keep your life as long as it’ll have you doesn’t mean you fear death,” I say. “Only that there are things left to do, and better times to die.”

He doesn’t look like he believes me. I don’t believe me beyond knowing that what I said is true, even if not for me. And I don’t want him to understand, either. This is personal, private, a sort of communion I’ve never had because I’ve never seen that fear, never taken it in both hands to feel its shape.

Was Four afraid?

“Whatever you have left to do,” Father says, “you have limited time to do it in. And whatever better time there is to die, I suggest you find it before you no longer have the option.”

Father’s right. About it going wrong.

I spend two days avoiding those frozen hours and then, lying in Noon’s bed in the velvet dark of early morning, I lose myself and whisper Four’s name into her skin. And the pause of her breath is enough to let me know she hears. She knows.

I wonder if she hears the skip in my heartbeat, too.

I wonder what I ever thought I had left to do, and all I can think of is her, making her at ease the way the rest were.

I wonder when, in my unchanging cycle of days, I thought would be best to die. The only answer I can think of is not now.

And then Noon’s hour begins to darken.

A wavering at first, like a hand before the sun, shadow flickering across the floor quick as wind. She came to me shaking the first time it happened, wondering if this was it, if she was turning to statue like those seven we move around with careful reverence.

“No,” I say, and my voice comes out even despite the jog-becoming-sprint of my heart. “I think this means your time is mostly gone, and now you’re mostly using mine.”

She doesn’t look any more comforted by this than I feel. Because my well is no more infinite than hers, and now I’m burning twice as fast.

“You should stop giving to me,” Noon says.

“What do you want, then?” I ask. “You want the knife? Or you want to become one of the frozen? I’ll let you go if you want it, Noon, but are you ready for it?”

Her fingers tangle in the loose, cool dress she wears, reflective deep gold that slips over skin like water over rock. “I don’t know. But I can’t do this to you anymore.”

“I do as I please with my time,” I say. “I’d rather burn out in service to you than to a universe we’ll never participate in.”

“I don’t want you to burn out at all.”

“I know.”

I place my palms over the white of her knuckles, and she leans her forehead into my collarbone.

“I feel like we’re running from something that’s just waiting for us to get tired,” Noon says. “And when we do, when it catches up to us, we’re going to be just as scared and unready as we are now.”

“I know,” I say again.

“What if we stopped? Not to go to it, or let it take us before we’re done. Just . . . walk instead. Let it catch us when it’s going to.”

I think about that, breathing the desert smell of her hair, feeling the weight of her against my bones.

When I get up, when I go to my drawers and take the knife, she doesn’t flinch. Just watches as I pull up my window and fling it out into the sunlight.

“Then we walk,” I say, and I don’t know what unknown she’s leading us into, but I know that I will follow wherever she goes.

I’d have called it denial if the losses didn’t stop being frightening. This is the difference, I think, between gritting your teeth to get through a thing and holding that thing close to your chest, growing used to its weight, its scent, understanding how to breathe and move around it.

These losses are natural in the course of losing ourselves. I keep Noon close to me when, at the edge of sleep, she jerks awake; Noon holds my hands when they forget that she is not Four, that there is no knife in her heart, that they still cannot, all these years later, keep Four together if only they can keep her blood from hitting the floor.

I don’t remember when Noon found the knife on her pillow. I do remember the cloudless peal of her laugh as she threw it from the spire’s peak, the glint of starlight on its blade as it fell, spinning, to the sand below.

There are bad days, too. Of course there are. There is an implied heat in burning out and there is an implied pain in heat. But the bad days are so much better with someone else, and there are still more good days than bad, and we still do our deft weaving of our hours, the humid gold of hers and the tongue-coating dark of mine at opposite ends of the day.

The rest of the hours look at us different now, and it takes me a few days to figure out why I recognize the particular cast of their gazes. They’re looking at us the way we look at those frozen seven. Fearful. Curious.

Reverent.

Noon’s days get worse before mine do. We knew they would. But they get bad so fast, and I wasn’t ready, and I want to be with her.

And that is how I come to understand something. Or I think I do. But I need her back with me to make it work, if it’s going to.

There’s little my dwindling supply of time can do for her, but I feed it to her anyway, waiting for her to come back to me, not caring how much it takes.

She surfaces slow, first blinking then clawing her way back up to now. When she sees what I’ve done, time dripping like tar from my hands, her face goes stricken.

“I thought we agreed no more,” she says. “Why —”

“I want to try something.” I fold her fingers in mine, not bothering to stem the dark flow of my magic. “The frozen ones. When do you think they are?”

Noon stares at me, uncomprehending, already descending back into that haze. I squeeze her fingers.

“Stay with me,” I snarl. “Do you want to go out together or don’t you?”

“Yes.”

Her voice is fuzzy still. I squeeze harder, enough it should hurt, and she flinches, clarifies.

“You’re hurting me,” she says. “Why are you —”

“If we take what’s left of our time,” I say. “All of it. If we use it to make a moment for ourselves. Do you think that’s where we’d stay when our time ran out?”

It’s been weeks since I’ve seen Noon light up this way. Her body straightens, her eyes glowing, leaning toward me.

“Do you think?” she asks.

“I don’t know,” I say. “But I like the idea of it.”

Her answering smile is sun peering from behind a scrim of cloud, so blinding white it etches light into anything it touches.

“There she is,” I whisper, and she’s the one to pull me up out of her bed.

It’s like the rest of the hours have an instinct about it, us hitting the bottoms of our wells.

We were in Noon’s room, at the top of the spire, and we collect the rest slow as we make our way down. None of them speak. They fall in behind us, drifting from their rooms and hallways on silent feet to watch us burn out in what will either be a lingering blaze of glory or a brief but dazzling flash.

By the time we reach the bottom of the stairs, the sound of our collective breaths has become something like wind, and there’s a faint strain of that metal-sweet scent of gravity, like Father is watching where we can’t see. I step barefoot from the final stair, and for the first time I am not crossing to the double glass doors alone and in the dark.

Noon’s hand is beside mine against the cooling glass, and we push the door open for the final time. The feeling in my chest is somewhere between ache and triumph.

We’re at the hours between us both when we leave the spire: sunset, the kind that puts on a show for summer in deep oranges and burning golds. The sand is coarse and sun-warm against our feet, and Noon pulls me to a stop.

“Are you ready?” I ask, and in response Noon dredges up all the time she can muster.

I join my time to Noon’s, and I’m immediately breathless, racing to keep up with the fast burn of her weaving, the deft twists of her fingers. I don’t ask her to slow. I don’t want her to slow. Because for the first time since Four, I’m not thinning my weaves, not taking ponderous steps alongside the other night hours. I’m rising to Noon’s challenge, looping strong curves of dark through bands of liquid sun and sky, shadow deepened by light and light strengthened by shadow.

As the rest of time wanes behind me, Noon pulls me close, fits our bodies together and pulls the threads tight. And if we are lucky, if a moment is all we need, then we might get to stay this way: warm and held, an eclipse where the lines of our bodies meet, a cleaving of noon and midnight that sears the eyes that meet it.

Host Commentary

Another perfect cap to our year is, of course, our End of Year Fundraiser, which could hardly happen at any other time of year. I’ll not belabour the details too much, given that there’s likely less than 36 hours left if the year even if you’ve sat with bated breath, refreshing your podcatcher feed to listen to this immediately, but this period of fundraising is often what sets us up for the year—not only with generous one-off donations, but with a bump in new Patreon subscriptions that then lets us plan for the year with confidence, knowing how many original stories (like this one) we can afford to pluck from the treasure pile, polish up, and show off to the world.

The very special thing about the year end fundraiser is that it once again has a matching fund from some of our most generous and long-standing supporters, so that every donation, and every new Patreon subscription—even and especially the annual ones, currently available at a 10% discount with code 2025YEC—gets doubled for us, so that every gold coin coming our way becomes two gold coins, which I am assured is not Faerie magick and so will not turn into autumn leaves at sunrise, but will remain a real and genuine gold piece we can spend on stories. And we do love stories, and we’d love to buy more, so if you were quick with catching this episode, and you’re quick with signing up, and you’re full of holiday snacks and cheer and generosity: please do head over to podcastle.org and take your pick of the donation buttons down the right-side column. And thank you.

…aaaaand welcome back. That was “Reverent” by Leah Ning, and it maintained the 100% perfect record of “Leah makes Matt cry” across her stories, so if you, too, crave the bittersweet release of crying on your commute of choice while everyone around you remains oblivious to your heartbreak, you should go back and find 915 (if you somehow missed it two months ago), The Hunter, the Monster, and the Things That Could Have Been; episode 768, The Consequences of Microwaving Styrofoam; and episode 679, Pull; and you should very much consider the content notes and whether you are in the place to deal with that topic, but if you are, my goodness. Then, after all that, you can go to Leah’s website at leahning.com for yet more.

There is never enough time. My gods, what a perfect story for this episode, at the death of a year, when we carve off another portion of our brief lives and file it away as the past: when we arbitrarily think of next week as the chance for a new start, a new path, even though it’s in our power to do that at any point in the solar orbit.

Time is the one true currency of our lives. We invest time in learning skills and knowledge, then trade more time using them both in exchange for our salary, to be permitted a comfortable existence—though at this stage of capitalism’s decline into a cover version of the French Revolution, we’re only getting “bare survival” in exchange now.

Away from our jobs, time is the currency we spend to show others that we love them, choosing hours in their company to no other practical end rather than the infinite selection of alternatives in the zero-sum game. It’s even encoded in our language, often without us consciously acknowledging the underlying truth of the phrasing: spending time, investing time.

And, as with all currencies, it only has worth because it has a limit. A finite supply. We were all taught about the consequence of hyper-inflation when a country tries to print money to escape a situation; gold has limited practical use but has been settled on as a cultural measure of value solely because of its rarity; De Beers are still trying to convince us that the provenance of mined diamonds matters even though we can make them in a lab now, cheaper and flawless and without, y’know, all the war and murder.

I am a committed atheist, have been since about 15, and am personally definite on the fact that there are no gods or divinities. This is, to be clear, a very personal view, and now I am not in my twenties and no longer pay attention to anything Richard bloody Dawkins says, I no longer hold any judgement of anyone else for their view: we each of us only parse a small fraction of the universe through our limited senses, one narrow band of the electromagnetic spectrum as light and colour, one narrow band of soundwaves as hearing, a random mishmash of once-important-to-our-survival chemical compounds as smell, all at a relatively narrow scale where both the macro- and the micro- extend above and below us for unimaginable orders of magnitude. I may very well be wrong! But I think Pascal’s Wager is rationalised cowardice, and that any divinity who would punish me simply for not acknowledging them despite otherwise always striving to lead a good moral life, well, they’re not a god worth acknowledging, nor hanging out with for eternity.

Anyway, point is that I don’t believe in eternity, certainly not as far as my own consciousness goes, and so my time is very much a limited currency. I’m early 40s now, so I’m about half-spent on what I’ve got according to the statistics, though who can ever know. I am at that famous mid-life junction where the approaching horizon is, if not visible, very much showing on the map. I am also closing out a year in which I have, through various bullshit reasons including the ease with which my professional role falls between the cracks of multiple teams, ended up working 400 hours of overtime despite all my best efforts to use it as I earn it. It’s been 140 hours in the past fortnight, when they were only paying me for 75.

And I am done sacrificing the time I should have with my family. Claire and I worked out earlier that the last time I actually spent a day with her, as my wife, was 26th November. I’m recording this on the 21st, before I drive back again—on a Sunday night!—to a hotel ready for another 7:30 start on site tomorrow. That’s bullshit. It’s bullshit of highest order, and it has to stop. I have to stop giving my time away like a charitable donation to a company that either does not notice or does not care, and I don’t know which is worse.

The only way worth spending my time is on the people I love. To spend it freely and with abandon in crafting perfect moments together, to see their smiles like “sun peering from behind a scrim of cloud, so blinding white it etches light into anything it touches”. There’s nothing I crave, nothing I ache for, more than that.

About the Author

Leah Ning

Leah Ning lives in northern Virginia with her husband and their adorable fluffy overlords. Some of the uncomfortable things she writes can be found in Apex Magazine, PodCastle, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and The Dark Magazine. You can find her on Twitter and Bluesky @LeahNing and on her website, leahning.com.

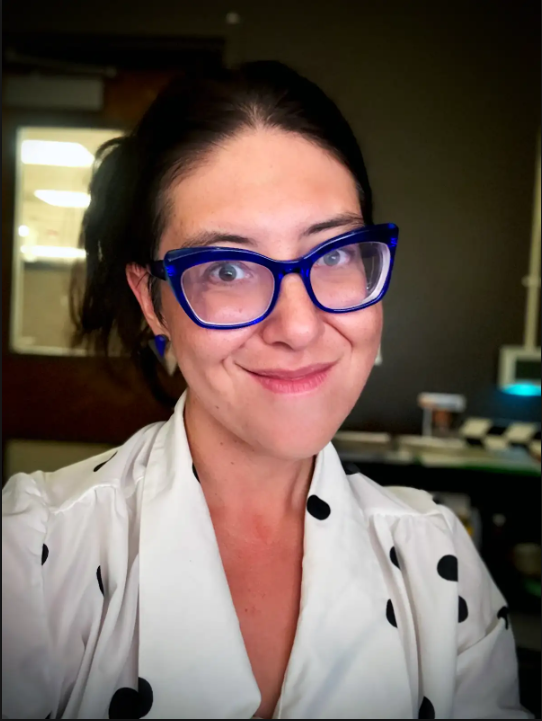

About the Narrator

Ibba Armancas

Ibba Armancas is an award-winning director/producer for KLCS PBS in Los Angeles. A voracious reader who’s been narrating fiction podcasts for over a decade, she makes optimistic educational media by day, and sci-fi and psychological horror by night.