PodCastle 890: The O’Brien and Palmer Show – PART TWO of Two

Show Notes

Rated PG-13

The O’Brien and Palmer Show – PART TWO OF TWO

by L. S. Johnson

INTERVIEWER: The war isn’t the only subject you delve into with this new show, is it?

PALMER: You know it’s not, or you wouldn’t ask the question.

INTERVIEWER: I have to say, we weren’t sure if we could ask the question at all, legally. You were quite the topic of conversation upstairs.

PALMER: Oh, I’ve heard that before. [laughter]

INTERVIEWER: Have you been afraid at all, talking so openly? That you might lose your audience, be fined, perhaps even arrested?

PALMER: Talk about what, John? [laughter] But do you see what I mean? I’m sitting here right before you and you’re avoiding saying what I am. We’ve got a bill sitting in Parliament, we have people demanding change, and yet we still can’t — or won’t — talk about what I am. Now you asked me about the war as part of my show. What kind of man would I be, that I could natter on about death and devastation, but fear saying what I am? What kind of society are we creating, where it’s acceptable to joke about genocide, but not to acknowledge the affection between two consenting adults? [applause]

INTERVIEWER: A very strong opinion, well put. Perhaps some of our politicians should take a few years off.

PALMER: You’d be surprised, the things you learn about yourself.

The little pub was tucked away in a cul-de-sac, just past the train station: the end of the line, and as such it was hardly ever crowded, and those who drank there kept their eyes on their pints. Anne had come across it when running a small circle nearby. It seemed a good place to meet, and better for the day proving rainy. When Mr. Palmer entered, placing his umbrella in the rack and brushing water off his trenchcoat, not a single one of the half-dozen people looked up.

He ordered a pint and made his way to Anne’s table, a wary expression on his face. She was already nursing her own pint, still trying to figure out how best to ask her questions. That he took the time to take off his coat and fold it neatly, to sit down and adjust his chair just so, made her wonder if he was also weighing out his words.

“Miss Wood,” he began. “If it cannot be done, you could have just said so on the telephone. We knew it was unlikely —”

She held up a hand, quieting him. He took a sip of his beer as she began speaking in turn, taking equal care with her words. “It is not impossible, Mr. Palmer. But it is a very risky undertaking. There is every chance that one or both of you could be lost in the process. You would both be dead, truly dead.”

“We’ve discussed that possibility,” Mr. Palmer said firmly.

“There is also the chance that one of you could be lost, and the body as well, leaving the other spirit alone but still anchored to this plane,” she pressed.

“And we have discussed that as well; we were going to ask that, if it comes to pass, you would do what you can to help the remaining spirit move on.” He continued when she started to speak, “we have weighed all the risks, Miss Wood. I appreciate your concern, but we have been debating this for over two years now —”

“It’s a chancey thing to have a spirit bound to an object,” Anne cut in. “If that photograph was somehow destroyed, you would lose Harry — yet it’s not clear to me where exactly he would end up. He might move on, or he might simply drift through the world, unable to materialize.”

Mr. Palmer was staring at her, his pint forgotten. “Again,” he said, a note of irritation in his voice, “we have considered all this. Why do you think I leave his things at home? I could have brought them with me on tour, but the risk was always too great. And even so, my heart is always in my throat: what if there’s a fire, or a break-in?” Before she could reply he continued, “ever since he came back I have done everything I could to protect him. This Timothy Palmer is a very precise construction, Miss Wood. Too fastidious for large dinner parties, too fussy to permit people handling his photographs or nosing in his cupboards, too uptight to go abroad or on extended tours; all that, and yet not too much, lest I be thought too queer, so queer I might be touched in the head.” His eyes were flashing. “Do you have any idea, can you begin to imagine, how exhausting the last two decades have been?”

“No,” she said quietly. “No, I can’t, Mr. Palmer. And therefore I have to ask: would Harry go to similar lengths for you?”

He stared at her for a moment, openmouthed in astonishment; and then his cheeks reddened, but from anger, not embarrassment. “You think Harry’s trying to trick me. You think he’s trying to steal my body.”

“Mr. Palmer, I have to be certain —”

“It was my idea.” He enunciated the words. “If anyone is exerting pressure in this, it is myself —”

A shadow fell over their table. They both looked up to see a ruddy-faced, elderly man beaming down at them, beatific with drink.

“It is!” he exclaimed delightedly. “You’re Timothy Palmer!”

A murmur went up from the others in the pub; Mr. Palmer’s face reddened further. “I am, thank you. Unfortunately I’m in the middle of a conversation . . .”

“Do the bit from ‘Once Upon a Wedding,’” the man said. “My missus loved that film.”

“It’s really not a good time,” Mr. Palmer said. “Though I’m happy to autograph something.”

“Oh, come on! It will only take a moment.”

“It’s really not a good time,” Anne echoed. She could sense Mr. Palmer’s rising agitation, see him trying to blink back tears. Over the man’s shoulder she looked meaningfully at the landlord.

“What, are you too good for us?” The man’s good humor was evaporating. “You do it on those talk shows quick enough. Or are we supposed to pay for it?”

“That’s enough, Eddie,” the landlord said, coming over. “They’ve paid for their drinks, not to have you bothering them.”

“Who’s bothering them? I’m a fan, that’s all!” Eddie let himself be led away, but he gave them a dirty look over his shoulder. “It’s his job to entertain, right? So what’s wrong with asking someone to do his job?”

Mr. Palmer took out a handkerchief and patted his forehead. “I need some air,” he muttered.

“Of course.” She swallowed another mouthful of her beer and quickly donned her coat; he was already grabbing his umbrella. Outside the rain was a gray drizzle that made them turn up their collars; Mr. Palmer opened his umbrella and held it over them both.

“I’m sorry about that,” he said.

“Why? It wasn’t your fault.” She glanced at him. “I’m just sorry you have to put up with that sort of thing.”

“I’m no good at it.” His tone was somber. “I was better when I was younger. I could laugh it off, perform on command. But even then it was never easy for me. Harry was always on, he would have done five different routines back there and had the whole place laughing. With me I have to make myself become that Timothy Palmer, and the older I get the harder it is.”

They were walking down the street; now they cut across to a small park with a gazebo. “I was in a sanatorium a few years back, did you know that?”

Alarmed, Anne looked up at him. “No. No, I didn’t know.”

“I was pressured into doing a full tour of the British Isles. I always kept my tours short, resting between, but this time my manager got the better of me. It was utterly grueling, just endless . . . and one day I simply couldn’t face it. I could barely get myself out of bed. Everyone had a fit, but I checked myself in voluntarily and brought Harry’s things in my suitcase. I was just so tired.

“It wasn’t supposed to be this way,” he continued as they reached the gazebo; he closed the umbrella and they shook water off their coats before sitting on the bench inside. “We were going to be The O’Brien and Palmer Show. Harry was going to be the front man, the personality. I was going to be the straight man, quietly undercutting him. It was so easy with him,” he added wistfully. “As natural as breathing.”

“But you recovered,” she prompted. “You went on, you’ve done shows since then.”

He nodded. “Harry talked me round. I had contracts to fulfill, after all. We wrote new material in the sanatorium: shorter, easier routines. But I didn’t want to leave. It was so wonderfully quiet. I worked in the garden, I watched television with the others three nights a week and the rest of the time it was just Harry and me. And that’s when I started thinking, it should be Harry onstage and me in the house. He loved performing in ways I never will. Oh, we’d still write together; I would watch television and listen to the radio, I’d stay up to date on the latest acts. But I could also be quiet.” He smiled wanly at her. “I’ll make an excellent ghost, Miss Wood.”

“You could be quiet now,” Anne pointed out. “You could retire, move to the countryside. You could even move abroad.”

He shuddered dramatically. “Abroad! What would I do abroad? I don’t even like pepper on my food.”

Anne laughed at that and he grinned, then sobered. “I wasn’t going to tell you about the sanatorium, especially not after you worked out we were lovers. I knew that if you believed me unstable you would never help us. But Harry says it’s not worth doing unless we’re completely honest with you; that if you helped us and then found out later you might regret your decision. And there’s enough regret in life already.”

“Mr. Palmer,” Anne said, “when did Harry first appear to you?”

“Hmm?” His expression had become faraway; and then he shook himself. “Not when I first got his things . . . I had been called up, you see, and I thought perhaps to get a memento of him, something I could carry with me. But his mother had cleaned out his room and found our letters; I came upon her just as she was throwing all his things into the rubbish.” He smiled bitterly. “We were lucky that I got there in time. The names she called me, right in the middle of the street, everyone watching . . . I haven’t been back to the neighborhood since. Harry says the one good thing about being dead is he finally hurt her as much as she hurt him.

“Anyway,” he continued, “I put his things in a chest and went off to do my service. When I was discharged I came home and got a bedsit in London, hoping to find work . . . I moved in, opened the chest to air it out, went for some groceries, and when I came home he was sitting on the bed, wanting to know where I’d been all this time and why my room looked so strange.” He gave a little shrug. “We’ve been together ever since.”

“One and done,” Anne said.

“One and done,” Mr. Palmer agreed.

His voice broke a little over the last; and then they just sat there, watching the rain fall steadily, casting a gray haze over the richly green trees and grass, bending the flowers with the water’s weight. Impulsively Anne laid a hand over his; he didn’t say anything, didn’t look at her, but clasped her fingers. Chilled, but alive underneath. And if she did this thing for him, and lost him in the process . . .? She looked at his profile, at the hollowness of his gaze. Two decades together in their strange union, a whole career built between them. The O’Brien and Palmer Show; they had managed it, even in death, even if it looked nothing like what they had envisioned.

“What would you do, if the switch succeeded?” she asked.

“Oh, Timothy Palmer will retire, at least for a few years. Give Harry some time to adjust, to work out what he wants. Then, if he chose to, he could make a triumphant return. A few years away would account for any difference in his presentation.”

“While you stay home, enjoying the quiet.”

Mr. Palmer smiled then, warmly. “He’s promised to prune my roses for me.”

But Anne only half-heard him. An idea had suddenly come to her, a possibly terrible idea; but it would ensure that, if she did pull it off, Harry couldn’t simply discard him.

“All right,” she said, as much to herself as to him.

He looked at her warily. “What does that mean?”

“I’ll do it.” She took a breath. “Though I warn you, it’s going to be long, and difficult, and I’ll probably damage your flooring —”

But she was smothered by his embrace as he hugged her. “Thank you,” he breathed. “Oh, thank you, thank you, thank you.”

They chose a Sunday morning, when the neighborhood would be at church or visiting and there was little risk of disturbance. Still they drew the curtains, and parked Mr. Palmer’s bicycle in the garage next to a brand new Triumph dusty from disuse. “I had to spend some money a year ago,” he said with an apologetic expression. “Something about taxes, too much savings.”

Back in the house she set about with her preparations. She had brought all her things in a nondescript hatbox, worn her coat over her best-looking pajamas, and splurged on a taxi; she needed to be as comfortable and energetic as possible. In the front room he had done as she asked, pushing all the furniture to the walls and rolling up the carpet. She grimaced at the lovely parquet flooring, but there was nothing for it; she opened up the hatbox and drew out her jar of paint. In the past they’d used salt, or earth, to draw the circle, but those materials were easily mussed, and Anne hated muss in the same way that Mr. Palmer clearly disliked disruption. So she had concocted her paint, a muddy paste laced with salt and several herbs that stayed put if layered on thick enough.

Mr. Palmer winced at the first dark smear. “How about if I make tea,” he said in a strangled voice.

“That would be lovely,” Anne said, scooping out two fingerfuls and continuing around the curve.

Harry drew close, curling over her shoulder, and she waved at him impatiently. “You’re dimming the light,” she complained.

Oh! Pardon me. He drifted to the far side of the circle. It looks complicated.

“The better to contain you both while I work,” she explained. When her circle finally closed she felt the click inside herself: the shadow jerked backwards.

Well. Not a charlatan, I see.

Anne grinned as she started drawing the pentacle inside.

Tim told me about your conversation.

“Oh?” She kept her head down lest he see her wary expression. From her hatbox she drew forth her notes and began drawing in the symbols, listening intently.

I have no intention of losing him, Miss Wood. We decided on something more substantial. To anchor him, as you would say. It’s on the sideboard.

She followed the line of gray air to a small jewelry-box. It was his father’s wedding ring. It fits his ring finger. He can come with me and it will keep the ladies at bay. Two birds, one stone.

“Are you worried about the ladies, Mr. O’Brien?” she asked.

They’re always crawling over Tim, and I’ve been told I can’t be rude to them. She distinctly heard a new tone in his voice: amusement, but tinged with jealousy. Really, a man of his age.

“It seems a little small,” she said.

That’s what she said! Whatever have you and Tim —

She exhaled in mock exasperation. “The ring, I mean.”

Should we find something larger? All the amusement was gone, replaced by seriousness.

She hesitated. “No . . . no, I like the idea of it.” Mr. Palmer entered, carrying the tea tray to the sideboard; she sat back on her heels and surveyed her work. “Getting there now. We’ll be up and running within the hour.”

“It feels warm,” Mr. Palmer said, lying on the floor in the center of the pentacle. “Is it supposed to be warm?”

“Warm is good.” Anne flexed her washed hands, and then took another pot and began painting her face. Surreptitiously she slipped the penknife into her pajama pocket. A way to pull the plug. She felt all but certain she would not need it, but the first sign of any malice from Harry and, well. With enough blood in the circle she could exorcise them both.

“Do you know, I’ve never lain on this floor before? There is a disastrous cobweb by the window.”

She glanced down at him. “We don’t have to do this —”

“No! Only it’s terribly annoying. How on earth did I miss it?” He looked to the sideboard. “Promise me the first thing you’ll do is go up there with a feather duster.”

Timothy Palmer, Harry said calmly, I love you more than life itself, but if this works I am not spending my first living moments dusting your molding.

“Oo-er missus,” Mr. Palmer replied with a smile.

Anne felt a pang. “It’s time,” she said gently.

“What do I do?” Mr. Palmer asked, while Harry said tell me where you want me, but he had already drifted close, bathing Mr. Palmer in shadow, almost protectively.

“You are both perfect,” Anne said, “just where you are.”

It was the longest spiritual anything Anne had ever done. She had practiced and timed it all, she knew exactly how long it would take and yet it felt so much longer, it felt like a week in the circle. Her whole world narrowed down to the two quicksilver essences with her, sliding back and forth as she guided and bound them in turn. For one brilliant moment they twined, and she nearly started crying then at the beauty of it, like stars merging in darkness —

And then the man on the floor before her opened his eyes, and it was at once Timothy Palmer and someone else, someone who opened his mouth wider to gasp and then breathe deep and hard, flexing his hands and trembling all over.

“Tim?” he cried. “Tim, where are you? Say something . . .”

Anne touched Harry’s hand, causing him to buck with surprise and fear. “Harry, it’s all right,” she said. Her voice was raw but she tried to sound soothing. “He’s as new to this as you are. It may take him time to work things out.”

Hold on, a voice faintly said, as if from a long ways away.

Harry burst into tears. He pressed Mr. Palmer’s hands over his eyes, then wrapped his arms across his face and breathed deeply, over and over. When he looked again at Anne his eyes were red. “Everything smells like Tim,” he said, and began sobbing harder.

I did bathe, Mr. Palmer said, more distinct now. A cloud of gray was coalescing beside them. You never said how hard it was to keep still! I keep floating every which way.

“Of course you bathed, you utter —” He broke off and sat upright, looking around wildly. “Oh no. Oh no. Oh God —”

“What is it?” Anne asked, laying her hand on his arm. “Wait! Don’t break the circle yet. What’s wrong?”

“The ring!” He pointed at the sideboard. “We forgot to bring it in! He’s not anchored to anything! We have to bind him somehow —”

“Harry.”

“It’s why he’s drifting! The moment we break the circle I’ll lose him —”

“Harry!” She caught his arms and gave him a shake. “Harry, it’s all right. I know we didn’t have the ring. It’s all right.” When he only stared at her, his eyes wide with terror, she managed a tentative smile. “Harry, I bound him to you. I bound him to this body. He can manifest anywhere you are; in fact, you’re kind of stuck with each other, now.”

You did what? Mr. Palmer cried, while Harry stared at her incredulously. That’s not what we agreed upon!

But she could not reply, because the man who had been Timothy Palmer and was now Harry O’Brien had flung himself on her in a bear hug, toppling them over and wrecking her neatly drawn circle.

“You marvelous, marvelous girl,” he gasped. “We are going to pay you so much money.”

Harry, are you sure?

“Of course I’m sure!” He shook his head, as if overwhelmed by the absurdity of the question.

You’re going to take me abroad, aren’t you? Mr. Palmer’s voice was resigned.

“I am going to take you all over the world.” He sat up on his heels and his expression softened. “Bloody hell. You’ve gone younger, darling.”

As you always looked to me.

“You all right, then?” he asked gently.

It will take some getting used to, but I’ll be all right. Are you all right?

He nodded, but he was weeping again; he wiped his eyes roughly with his sleeve. “No one has ever . . . I mean, what you’ve done . . .” He looked up, then laughed and held out his hand, as if wiping tears from the darkened air.

You are worth it, Mr. Palmer said, and his voice was stronger now; Anne could almost see his earnest expression, the gleaming eyes. You were always, always worth it, Harold O’Brien, no matter what your mother said. And then, before Harry could reply, just remember you promised to prune my roses.

“More tea, vicar,” Harry replied with a sob, and they all laughed at that, Anne too, laughing through her own tears; Harry glanced at her, then leaned over and squeezed her hand. “I’ll make the entire damned garden nothing but roses,” he said, his voice quavering. “The neighbors are going to hate us for all the bees. It’s going to be marvelous.”

INTERVIEWER: Tell us about that second summer.

PALMER: Well, my roses were blooming [laughter] so I decided to travel a little. I never toured abroad in my younger days; I always thought of myself as an English comedian, that my humor would only really land in England.

INTERVIEWER: But something happened while you were traveling, didn’t it? Something changed you.

PALMER: Well, I had already changed, I was changing. But when I started traveling, I saw all these young people, not just sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, but fighting to be honest about themselves, fighting to make the world better. Being themselves in public and saying “this is who I am, I have a right to love.”

And I thought of all those lost in the war, so many young men gone. What did they die for, if not the right to love? How was I honoring their memory by hiding? Don’t get me wrong, I don’t regret hiding, nor do I think anyone hiding right now is foolish for doing so. I never would have had this career if I’d been out, as they say.

INTERVIEWER: You’re saying that people wouldn’t have hired you, knowing you were homosexual?

PALMER: I’m saying people wouldn’t have hired me if I spoke about it publicly. You could be, you know, swishy, but you could never talk about it. But now here I was, secure for the first time in my life. Career, finances, in myself: I have everything I need right here now. [he touches his chest] I don’t have to fear anymore. I can do as I please. I can even support the Sexual Offences Act. [applause] [to the audience] Go forth and vote, my children! [laughter and applause]

INTERVIEWER: I must say, when I interviewed you, what, eight, nine years ago? I never imagined we would be having this conversation now.

PALMER: Well, that time away helped me feel whole again, for the first time in years, decades even. And I realized what I truly wanted was to help others have it easier than I did. Leave the world better than I found it, right? [applause] Love can do impossible things, John. I’ve seen it firsthand. But it begins with believing that it’s real and you’ve a right to it, whatever form it takes.

Host Commentary

So! Final warning that THIS IS PART TWO, GO LISTEN TO PART ONE FIRST BEFORE I RECAP RIGHT NOW. We opened on a television interview with one Timothy Palmer, a performer returned to the public eye after some time away, before swiftly cross-fading into Anne, a medium who finds the world doggedly going out of its way to show her an advert seeking a medium for a private séance. When she arrives at the address, she is greeted at the door by, of course, Timothy Palmer, and once inside the living room, she is introduced to the ghost of Harry. After overcoming her shock with a cup of tea, Mr Palmer relates how he and Harry had known each other since childhood, until Harry lied about his age to enlist for the war, being killed on the front only a month in. He then lays out the proposition he wishes to discuss with Anne: that he, Mr Palmer, has had a decent run at life but never truly felt like he loved it, not like Harry did, and that all things considered he would like, now, if possible, to trade places with Harry, such that the latter could live in the corporeal world once again with Timothy now the ghost. Anne, without much difficulty, intuits that Tim and Harry were lovers before the latter’s death, and it is this love that has bound them together for all the decades since, as invested—grounded—in a photograph of the two of them twined together on a beachside foreshore. She departs to do some research in how the process might unfold, and to seek advice from a fellow medium, who warns that the spirit may be simply pretending to be Harry as a way to get back to the physical world, and that if this goes wrong, Anne may very well end up haunted by the dispossessed spirit of Mr Palmer.

And now pay attention, for our tale is about to resume, and conclude…

…aaaaand welcome back. That was “The O’Brien and Palmer Show” by L.S. Johnson, and if you enjoyed that, and were moved by that, then we have three other stories from her in our archives: 652, Apple; 528, Properties of Obligate Pearls, which I adored; and 521, We Are Sirens.

LS sent us these notes on “The O’Brien and Palmer Show”: I was thinking about 1960s-70s British comedians when I wrote this, and I was thinking especially of the ones who were practically caricatures of queerness – Kenneth Williams, Frankie Howerd, Melvyn Hayes – and how exhausting that must have been, to be that persona for so long.

Thank you, LS, for the notes and for the beautiful story. The ending gives me goosebumps. The ending gives me hope, frankly, because right now this rancid little island I live on is tying itself in the most incredible, idiotic knots over trans rights, with a Supreme Court judgement that is being twisted by the most godawful people to apply to situations and circumstances far beyond the original case and in defiance of the still-applicable Gender Recognition Act in, apparently, a beat-for-beat cover of the Section 28 travesty of the 1980s. Section 28, for those of you fortunate not to live in such a benighted and bigoted land, was a law introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s government of the day to forbid local authorities to “promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship”—those are the actual words of the legislation. Of course, the definition of “promotion of homosexuality” was left vague such that it had an outsized chilling effect, with teachers unwilling to reference the subject in any context for fear it would fall under the definitions of this law.

Section 28 was part of the Local Government Act 1988. It was only repealed in 2003. This is not distant history: 2003 was the year we were all shout-singing along to Bring Me To Life by Evanescence, for goodness’ sake. More pertinently, 1988 to 2003 was exactly my UK school career, from reception to upper sixth. My secondary school was between seven to eight hundred pupils, and not a single person was openly out as anything other than straight in the seven years I was there; this is not the same as saying there were no queer people in my school, as subsequent Facebook posts on my feed have shown.

1988 was, of course, also the height of the AIDS crisis, and all the media panics about what if gay men sexually assault other men in toilets and changing rooms, and other such nonsense fundamentally predicated on a fear that gay men might treat other men the same way that straight men treated women. And now, in 2025, we find ourselves with schools being told they shouldn’t discuss transgender or genderfluid identities, that they shouldn’t support students wishing to transition and should inform parents regardless of the student’s wishes, with a constant and incessant media panic over trans women attacking other women in toilets and changing rooms… and I know they say history doesn’t repeat but only rhymes, but my goodness this is like one of those cover songs that’s indistinguishable from the original. How can you be spouting all this anti-trans stuff in exactly the same pattern as the gay panic you lived through yourself and not be acutely aware you are on the wrong side of history here?

I left school myself in 2003, four months before the repeal of Section 28. But after university, my first job was back in a school, not five years later; and already there were students who were loudly and proudly queer, and in the 17 years I’ve worked in and around education since, that has only gotten more true. The kids are not only unafraid to be queer, they are there for each other, and back the right of anyone to love anyone—usual teenage dramas aside, of course. And so yeah, right now things seem pretty dark on this nasty little island of intolerance—but they seemed dark before, and in the end the light won out, and won out so fiercely that the generation below me have never even heard of Section 28, can’t even fathom such a thing existing. We’ll get there again: I just wish, so sincerely and deeply, we didn’t have to see so many people hurt along the way.

About the Author

L. S. Johnson

About the Narrators

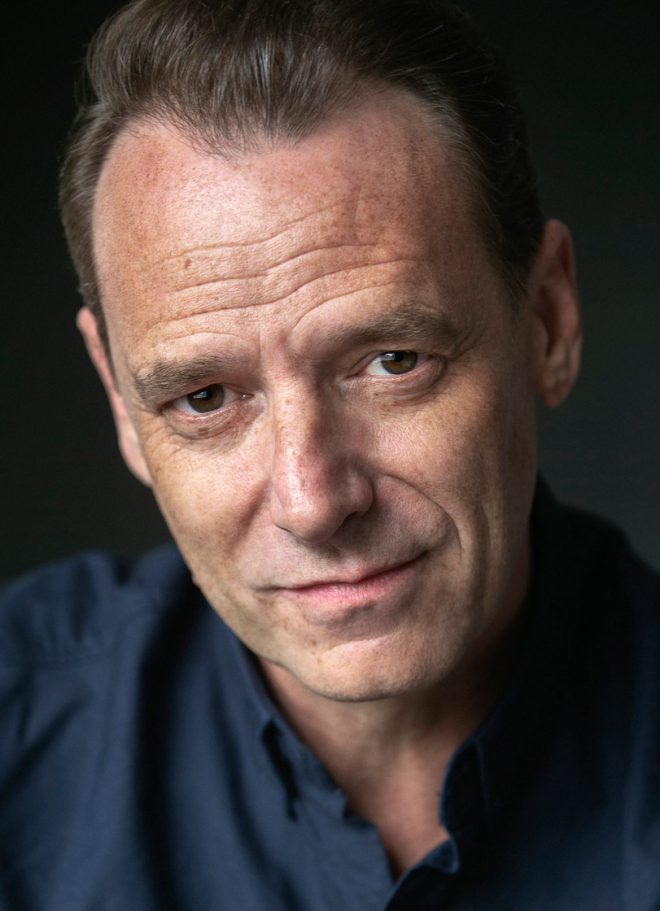

Peter Seaton-Clark

Peter is a British stage and screen actor who is also a naturalized German citizen. Born in Barnstaple, England, he started his acting career on stage at the world famous Leeds City Varieties in 1994. Other regional theatre engagements were followed by a stint on local TV as a presenter. Moving to Europe he took on more voice work and became a founding member of an English speaking theatre company in Leipzig, Germany. He is known for Uncharted (dir. Ruben Fleischer), the award winning short film Swiped, in which he starred and produced, as well as Coronation Street in the UK, Gute Zeiten Schlechte Zeiten in Germany and the Russian films Chempion Mira and Diversant IV. His upcoming TV projects include the international production Concordia.

Nicola Chapman

Nicola Chapman has worked professionally as an actress for over thirty years in TV, film, radio and internet. Her voice-over experience includes TV and radio advertising, singing jingles, film dubbing and synchronisation, training videos, corporate films, animation, video games and Interactive Voice Response for telephone menus. She spends most of her time running her voice-over business, Offstimme, which sources and provides translations, subtitles and voice-overs in over 40 languages. She has been known to write a story or two, purely for her own enjoyment, but she loves bringing other people’s stories to life in the studio.

When not working, reading or playing with her cats, Nicola can often be found up to her elbows in flour, trying to make the perfect brioche. This may take a while….

Matt Dovey

Matt Dovey is very tall, and very British, and although his surname rhymes with “Dopey” all other similarities to the dwarf are only coincidence. He’d hoped for a more exciting mid-life crisis than “late autism and ADHD diagnoses”, but turns out you don’t get to choose. The scar on his arm is from an accident at the factory as a young ‘un. He lives in a quiet market town in rural England with his wife, three children, and varying quantities of cats and/or dogs, and has been the host of PodCastle since 2022. He has fiction out and forthcoming all over the place: keep up with it at mattdovey.com, because he’s mostly sworn off social media. Mostly.