PodCastle 837: Good Fortune For a Beloved Child

Show Notes

Rated PG-13

Good Fortune for a Beloved Child

By Alexia Tolas

There ain’t no body for Thomas funeral, so we bury an empty coffin.

Not empty, Daddy did tell me as we followed the undertaker to the cherry-woods and mahoganies. The coffins they pretty up with ivory velvet and pillows and other shit the dead ain’t gonna care about ‘cause they dead. We don’t even know if Thomas really —

Quintia . . .

But I hear him at night. Singing.

Please!

When the tide goes out.

Enough!

The undertaker cleared his throat. Daddy nodded at the mahogany for $6,000.

For his mother’s sake, enough.

His mother.

Ain’t she my mother too? That’s what she told me the day we picked up the adoption certificate.

Since there ain’t no body to bury, we filled the coffin with the pieces of Thomas we find around the house. A softball glove. A crawfish spear. His favorite rashguard. There’s still pieces of him on the sleeves. His smell — sun-tan lotion and sugar apple. A strand of his yellow hair. I tried to keep it, but Daddy said Thomas needed to be laid to rest.

Mummy don’t want Thomas to rest. She near dead when she see Daddy pack the rashguard away with the other pieces of her child. Her cries did shake the walls. Her tears flooded the tubs and sinks. She did sink her words into the box, and with every plea and threat, she take back another piece of Thomas.

Was the coffin a dumpster?

Was Daddy that eager to give up on his one child?

Was Thomas so easy to replace?

But you can’t blame her for being angry. Every day there’s more and more blank spaces in Thomas room. And the more Daddy take away Thomas, the more he fill up the house with me.

I can feel her eyes burning through my skull as I walk up to the coffin to pay my last respects. Daddy and I avoid her hate by taking the side aisle back to our pew instead of the center aisle Mummy takes to the nave.

Mummy. That don’t sound right in my head no more.

Of all people, she should’ve believed me. She who follow Thomas singing to the bluff every night. She should’ve been happy to know that I too hear his voice riding the white caps to shore. But that ain’t all I tell her. I tell her something I ain’t tell the police. Something I ain’t tell Daddy. I tell her about the wet girl. The wet girl with barracuda teeth and backwards feet who pulled Thomas into the sea.

I run my tongue along the gash inside my cheek. That’s how hard Mummy slapped me.

Mummy rests her hands on the coffin, and a hush falls over the congregation. There’s a knowing in the people, a knowing I can touch but can’t feel. There ain’t no separate sorrows, just one mourning, like a song with many voices. Is not like the sorrow at my grandmother’s funeral where two of my aunts tried to jump into the grave. The wails at Grammy wake can’t compare to the stifling anguish in this room. What’s more, it’s a secret anguish, one that don’t show itself in tears (because there ain’t a wet eye in this church) – or in screams (because it’s so quiet I can hear my own blood rushing through my ears). It almost feels like . . . defeat.

Maybe I’m still too new to Keask Bluff to be in on the secret. It don’t matter how red and puffy my eyes is or how much my gut burns or how my heart feels like half of it’s dead and the other half has to pump that much harder to keep me alive. These people singing together, and I’m a discordant chord.

Mummy touches her head to the coffin and whispers something. We can all hear it. It gets louder and louder as she turns to look at me, her skin squeaking against the polished mahogany.

“It was supposed to be you.”

It was too good to be true.

Everybody in Abaco knows Keask Bluff ain’t a place for girls like me. Girls whose mothers snort coke. Girls whose fathers sell coke. Girls whose grandmothers clean the green, blue, and yellow houses that line the coast along the Little Bahama Bank like glass beads on a bracelet. But I managed to slip through the tall, pink walls of the gated community. It was the first time I ever see the gates open. Even when Grammy cleaned for the families behind those gates, she never passed through them. She and all the other day laborers had to take the side gate that run through jumbae and gravel.

Benjamin and Ashley pretended to know Grammy. They talked about her as if she’d baked bread in their kitchen and wiped their son ass when he was a baby. I wasn’t surprised they knew of her. Grammy worked for Keask families all her life. She was one of the only local dailies Keask ever allowed into the community. A lady from church said once that Keask people prefer Haitians and Filipinos who can’t complain to the Labor Board if the pay low or the hours too long. Most people say it’s because Keask people don’t trust you if you too black. One lady who head bad-bad said it’s because long ago a Bahamian maid did leave a window open in the laundry room and a snake got in. Eat the boss-man baby up. Stupid woman. Who ever heard of garden snake eating baby?

Grammy never pay those stories any mind. I figure that’s why Keask people liked Grammy so much. She was quiet. Did keep her business to herself and other people business to God. Our neighbors used to try pick my mouth for the secrets Grammy collected, but all I knew were the names of the people she worked for, and not one of them was any Benjamin or Ashley Saunders.

So how this Keask couple did find themselves in Cooper’s Town Evangelical and why, neither me nor Pastor Ferguson knew. But they asked for me by name. They wanted to know what would happen to me now Grammy was gone. Pastor Ferguson did throw me one quick look and frown.

The Children’s Home in Grand Bahama. Maybe the Ranfurly Home for Children in Nassau.

Ashley eyes water. She pushed her blond hair behind her ears and then took my hand as if I was her dearest friend.

Come live with us.

It was too good to be true. That’s why I didn’t wanna go.

Where they was all these months I been passed about like one ugly Christmas sweater? I asked Pastor Ferguson.

They here now, Quintia, Pastor Ferguson said as he watched the Saunders from the corridor.

I could smell Benjamin and Ashley in the rectory kitchen. It was a smell Grammy did bring home in hand-me down clothes and bed sheets. The smell of lavish houses on the canal. Boats docked at the back porch. Golf carts and big trucks. The Keask smell. I ain’t catch a whiff of it at Grammy funeral.

That’s why I didn’t wanna go.

But in the end I did, and even though I knew it was too good to be true, it was true for a while.

And it was perfect.

I rest a speargun on the marine store counter. Freddy glances at it and snorts.

“What you gonna do with that, girl?”

So, it’s “girl” now? I used to be Quintia. Maybe not always. Sometimes it was Quinisha, sometimes Quinta, but at least Freddy used to try. Everybody in Keask used to try until Thomas disappeared.

I pull out my credit card. Freddy tilts his head. Sneers.

“Benji musee like wasting his money on shit.”

Somebody chuckles behind me. They don’t even pretend to look at fins and goggles.

“Shit like this?” I tap the speargun grip. “Illegal shit?”

Freddy ain’t laughing when he swipes my card.

Thomas never used a speargun. Said the law was to protect crawfish from cheating, greedy bastards. Still, he showed me how to use one in case anything with teeth come along while we was deep-sea diving. Eel. Shark. Barracuda . . .

The police tell me there was nothing I could do for Thomas. He might’ve pulled me underwater and drowned us both. But how could he pull me down if he wasn’t fighting? How could I save him when he didn’t wanna be saved?

With her mouth closed and her feet covered with bay lilies, the wet girl almost looked beautiful. Long black hair. Skin white-white like shad belly. And wet. So wet you could see right through her clothes to the dark nipples underneath. The patch of curls in between her thighs. And the way Thomas looked at her. Like an animal ready to rut.

Dakota waiting for me when I get home. She sitting with Daddy on the couch, holding his hand. When they see me, Daddy wipes his eyes. Gives me a smile. He don’t want me to know that Keask Bluff blames me for what happened to Thomas. That Mummy blames me. I put on my own smile so he don’t know I blame myself too.

“Why buy one?” Dakota says, shoving the speargun under my bed. “Uncle Benji got plenty.”

Rail guns. Roller guns. Pneumatic guns. How else could Daddy catch so much crawfish and grouper?

I twine a piece of black-and-white snakeskin through my fingers.

“I don’t want him to stop me.”

Dakota takes the skin.

“Thomas gone, Tia.”

“You don’t know that.”

Dakota balls up the skin and shoots it into the trash bin. Then she pulls me into her arms. Her honey hair tickles my cheek. I take a curl between my fingers.

Just like Thomas.

“You gotta let him go, Tia. Aunty been through enough.”

Mummy had a sister once. She gone for a swim one morning and never came back. That’s why when the police tell her about Thomas, Mummy did keep saying Not again!

Not again!

There’s a slam downstairs. The smell of seaweed and Aristocrat. Mummy’s home.

But she won’t be for long. She only comes home to clean herself up. Maybe nibble on one piece of fry bread. Set her head on a pillow long enough to keep her brain from turning to mush. Then out the door she’ll go — back to the bluff to listen to Thomas sing.

There’s a scuffle. I picture Daddy trying to hug Mummy. Maybe stroke her hair. But that ain’t what she wants. He can’t give her what she wants.

Now come voices. Hushed at first. Then hysteric.

“Two hundred dollars, Benji!”

Dakota glances at the speargun under my bed. A lump like a mango seed bulges in my throat.

Daddy laughs. Says something about shoes and nails and the salon.

Mummy roars. It’s a half-scream-half-dying thing.

“I can do whatever the fuck I want with my money!”

The walls shake. Soft whimpers now.

“Ain’t I earned it?”

More scuffling. They trade whispers.

“No!”

Dakota looks at me. That’s Daddy.

Mummy voice too low to make out sentences. Just words. Grand Bahama. Ranfurly . . .

“She ain’t a dog, Ashley. She’s your daughter!”

For a moment there’s quiet, a quiet that says it all.

In maps of Abaco, it’s Keask Bluff, but behind the gates it’s Ceasg.

Because that’s how it’s spelt, Benjamin did tell me when I asked him why even my new private school spelled the settlement name so funny. He wasn’t Daddy yet, and because he wasn’t Daddy yet, I asked a lot more questions.

Maybe Thomas can tell you what it mean.

But this was when Thomas still hated me, so all he did was give me a look that could melt brick.

Dakota did tell me one version of the story. Way before the Loyalists arrived, a Scottish man named Russell did gone fishing after a hurricane. He cast out his net, hoping for some shads or grunts, but he snagged something much bigger.

A mermaid, she said. Grammy would’ve called it Water Mama. But Dakota called it “ceasg”. That’s the word the Scottish man Russell used.

He made a deal with her, Dakota said, He’d set her free, and she’d grant him a wish.

I asked her what the Scottish man Russell wished for. Dakota smiled. It wasn’t a happy one.

That we would prosper.

It was a convenient story. A mermaid — not illegal fishing and drugs — made Keask Bluff rich. Behind that story, Freddy could sell his dynamite and spears and long-haul nets. Grammy bosses could dump their hand-me-downs on the poor and spend their drug money with a little less guilt. The settlement could let one little Black girl through the gates and hide from the rest of the country. I prefer the story Thomas would tell me when he didn’t hate me no more.

I think about that story in front of the television, but then Daddy pulls me out of my thoughts when he sits next to me with a bowl of popcorn and M&Ms. He takes my hand and squeezes it.

A girl’s got to be smart when she’s alone in this world. Too many people tried to play me for a toy when Grammy got sick. I was sure the Saunders had their own game to play when they came looking for me.

Why take me in? I asked.

Benjamin squeezed Ashley hand and smiled.

Because you deserve to be loved.

And I believed him, you know. I believed him because I did done see so many smiles in the months leading up to Grammy death, some seeping bitterness when I asked for lunch money or tampons. Some with hairy hands that travelled up my thighs. So many smiles wasn’t really smiles, but Benjamin smile was.

And he did keep that smile whenever Ashley would say dumb shit like —

Quintia. What a special name. Was your father’s name Quinton?

He did keep that smile when he massaged coconut oil into my scalp, parting each strip of hair with a steel pin comb like he actually knew how to box braid.

He did even keep that smile the first night we was left alone. Thomas got bite by something in his bedroom, so Ashley did take him to the clinic. I cringed when Benjamin did sit beside me on the couch. But then he turned on the TV and passed me the remote.

Popcorn or M&Ms? Or popcorn with M&Ms?

Two months later, I called him Daddy by mistake. He ain’t never correct me.

I hear Ashley behind us shuffling down the stairs. She slams the front door so hard the TV shakes.

“Give her time,” Daddy says when he really means It’s not your fault.

“She hates me.”

And I hate her too. I can’t even fix my mouth to call her Mummy anymore. Tastes sour.

Daddy pulls me close.

“She love you.”

Ashley tried to love me. She really did try. She tried to grow the love between us with mani/pedis and brunches. She tried to show her love in awkward hugs and kisses. But love ain’t never come naturally between me and Ashley. She wasn’t even jealous when I started calling Benjamin Daddy. She only asked me to call her Mummy when Thomas started sneaking the girl into his bedroom.

What girl?

Thomas glared at me over his eggs. Like I was the one betraying him. I said “Hmph!” and nibbled on my corned-beef hash while Ashley waved her spatula around, demanding answers.

It did feel wrong when I tell Ashley about the girl, but I couldn’t help it. When the laughter from his room started, everything between me and Thomas changed. He stopped spending time with me. He’d walk home from school alone. He’d hide in his room like a soldier crab. It was like he forget about the night by the sink hole. Maybe he wanted to forget . . .

So, I indulged Ashley. I helped her punish Thomas by sucking up all the love she take from him and give to me. We went on trips to Nassau without him. We splurged in couture stores. We held hands as she got my name tattooed on her left breast. Much closer to her heart than Thomas name. Secretly, we enjoyed hurting Thomas as much as he hurt us, and because we didn’t know what to call that thrill we got together as we punished him, we called it love.

But it wasn’t love. If it mean getting Thomas back, Ashley would throw me into the sea herself.

That’s why when I meet her by the bluff tonight, I’m surprised she stops me.

We stand there for a while and listen to Thomas voice riding the waves. Ashley looks at the outline of the bluff looming over the sea.

“Benji know you here?”

“No.”

“He won’t forgive me if you go.”

My grip tightens around the speargun in my hand.

“But you want me to.”

A long, mournful chord breaks against the sand. Ashley closes her eyes. Breathes in droplets of Thomas.

“Yes.”

Been a fortnight since Thomas walked into the water. And now, on this new moon night, I walk in too.

In his defense, Thomas said he didn’t wanna love me.

He whispered it into my mouth just before our lips could touch. It would be better for me, he said staring into the pool of water below us in the cenote, if he didn’t love me.

The sea is quiet. I tread the surface with my torchlight. Secure the speargun in its holster. I wade into clear, tepid water.

The bluff was the perfect place, Daddy said, to teach me how to swim. Thomas wouldn’t take me out in his skiff until I learned. The limestone cupped the shore like a hug, creating a wide basin with just enough space between the hands to allow the flow of the tides.

We all knew Thomas was bluffing when he demanded I learn how to swim. Thomas did think I would refuse, scared as I was of the water. But he embarrassed me at my welcome party. Everyone in Keask had been so kind. They did give me gifts. Talked to me. Made me feel loved. Everybody except Thomas.

At first, he didn’t wanna leave his room. When Ashley finally dragged him downstairs, he did hang around like a storm cloud. And then the yelling started. Ashley tried to keep it in the kitchen, but rich people like open-concept houses. They forget that island people build walls to hide the dirty things.

Lies, he said.

Love, she said.

He laughed a cruel-cruel laugh.

Disgusting.

And then a slap so loud Keask Bluff did freeze.

I let Thomas teach me how to swim to prove him wrong. That I wasn’t disgusting. That it was his family who came looking for me. After my first deep-sea dive, I was ready to rub my victory in his face, but then he smiled at me. He praised me at the dinner table that night. And then, our knees touched under the table, and he blushed. He had me. Hook, line, and sinker.

There ain’t no current tonight. I wade through the water until I can touch the limestone base of the bluff.

There’s tunnels under the bluff. Some lead you out to the ocean. Some run deep into the earth. Thomas did tell me the ceasg lives at the end of the biggest tunnel. Even if he didn’t tell me, I would know. That’s where his voice coming from.

The water hugs me tight. The tunnel even tighter as I wiggle through the shaft. Just as my lungs feel fit to burst, I break the surface and find myself in a tall, wide cave.

The pool I wade out of laps quietly against a raw limestone platform. I hear the ssh-ssh-ssh of snake bellies. My torchlight falls over a scattering of bones. Some fish. Some not. There’s a bend in the cave like the end of a comma. From there Thomas voice calls me. Strong. Like when he’d belt a solo at church. Sweet. Like when he’d race his skiff against the wind. I follow the voice around the bend.

She smiles when she sees me, as if she knew I was coming.

Mermaid. Water Mama.

“Ceasg.”

She bares her barracuda teeth, but she don’t move from her pool. Over her shoulder peeps a tiny black-and-white snake.

That day at the beach, I did know she was the girl who was sneaking into Thomas room. I could hear it in her laugh. For weeks she’d cast a spell on him in secret, but I stiffened my back, begging her to try steal him from me if she did think she was woman.

Then she moved out from the bay lilies. “Moved” because stepped would be the wrong word. She’d glided over the sand and pine needles without ever moving her legs. When I looked at her feet, I choked. Backwards. Like duppy.

But Thomas smiled. His green eyes was black. His jaw slack. And when she glided backwards into the water like a lure on a nylon line, he followed. No matter how loud I screamed, Thomas didn’t hear me. She’d hooked him with that crooked barracuda smile, and then she’d hauled him into the ocean.

Here in the pool, she ain’t pretending to have feet no more. She flips a long, gray fleshy tail. Like a dolphin. She pulls herself up on the edge of the limestone shore weakly, fingering a strange white ribbed tube.

“Waited for the new moon.” She laughs. “Clever girl. What you come for?”

Her smirk tells me she knows.

“Thomas.”

Giggles ripple through the cave.

“How you mean to come take what’s mine?”

She’s right. Thomas is hers. The Scottish man Russell sold him centuries ago.

“You done take from Ashley before.”

Wasn’t that the deal? For Keask’s good fortune, one family must sacrifice a beloved child. One child every seven years.

She took Ashley sister last time, Dakota did tell me when I showed her the skin from the snake that did bite Thomas all those months before. The snake that did sneak into his room every night.

“Ashley sister was a Christie,” the ceasg says. “Thomas was a Saunders.” She licks the white ribbed instrument and laughs.

“That’s not fair.”

The ceasg raises a coy brow.

“You want him back?”

She places the white ribbed thing to her lips and blows. Thomas voice echoes against the cave walls.

“Gotta remind them sometimes what their fortune costs.”

She tosses the larynx. It lands at my feet with a wet thud.

I feel the speargun’s grip at my cheek before I know what I’m doing. I’m pointing it at her head.

The snake on the ceasg shoulder hisses, but there ain’t no moon to give it strength. But she don’t need the moon to hurt me when she laughs.

“You loved him. That’s why he did taste so sweet. Love season better than salt!”

I pull back the safety. If I miss her head, I might hit her heart.

But the ceasg pays me no mind.

“You should be grateful, Quintia.”

My finger tenses against the trigger.

“Want to know how I get your name?”

One pinch, and that’s it. For Thomas.

“They give it to me when your Grammy dead.”

My finger goes slack. I nibble her bait.

“Tried to give me you instead.”

My mouth goes dry. She tugs on the line.

“Tried to hide their real child by fattening up a fake sacrifice with love.”

Ashley words at the funeral come back to me.

I lower the speargun. I know now why the Saunders came for me. Why Keask Bluff tried so hard to love me. Why their love disappeared when Thomas walked into the water. Why Thomas didn’t wanna love me at all.

The ceasg lowers her body into the water. She almost looks sorry for me.

It was supposed to be you.

Host Commentary

…aaaaand welcome back. That was “Good Fortune For a Beloved Child” by Alexia Tolas, and it was her first time—though assuredly not her last–on an Escape Artists podcast, but if you enjoyed today’s story then a quick search of her name will bring up a couple of others that are free to read at Adda Stories: “No Man’s Land” and “Granma’s Porch”

So far as possible, I aim for eloquence in my outros, hoping to express in words the complicated mix of emotions an author has engendered with their telling. To that ending, though? The only thought I have is oof. What a punch.

I can’t speak for Alexia as to whether this was intended or not, but my goodness, the metaphor for climate collapse and who is going to pay the price is not hard to see here. Making a deal with a force of nature for your temporary enrichment, at the cost of your children? Trying to arrange it such that Black and brown children pay the price instead of the white folks in their gated community—be those gates on the small scale of a community, or the grand scale of national borders increasingly closed to refugees? I suspect it’s not an accidental allusion, frankly, even if it wasn’t conscious, given that Alexia is from an island nation, one that will be among the first to pay the price for our hubris and greed, for decades of selling out our future for a little short-term prosperity and quarterly growth.

The answer to this real world conundrum is the same as the answer to the story’s, too: to refuse the bargain, to accept that prosperity must be won through hard work instead of exploiting nature, and that perhaps that prosperity ought to be more restrained rather than endless, endless, endless. But, as in the story, that’s so unthinkable to some people that it must not, cannot be mentioned. The community of Keask Cliffs apparently never even contemplate it as an option, and instead go to tortuous lengths to try and sacrifice the right kind of child, in their eyes, instead of finally acknowledging this devilish deal and turning from it; likewise we talk now of limiting ourselves to 1.5C above baseline, maybe 2C, and the resulting damage will of course be enormously regretful, we’re so sorry for it, there was simply no other way! Because the idea of just… turning off the oil tap is almost literally unspeakable.

We have the technology now, and certainly the money, to just make the switch, almost overnight. By the next turn of the decade we could all be in electric cars in developed countries, powered by a grid made of solar and wind, but we simply… don’t have the political will, when it will overwhelmingly not be the children of those developed countries paying the price. We can continue to globalise the suffering, outsource it out of sight, after all, as we do with so much of modern consumerism—and never mind that what is truly consumed is our future.

About the Author

Alexia Tolas

Alexia Tolas is a Bahamian writer whose narratives explore the intricacies of small-island life, drawing heavily from local folktales and mythology. Her writing has been featured in literary journals including MsLexia, Granta, Windrush, Adda, and The Caribbean Writer. She won the Commonwealth Short Story Regional Award for the Caribbean in 2019, shortlisted for the 2020 Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award, and in 2022, she received the Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival’s Elizabeth Nunez Award for Writer’s in the Caribbean.

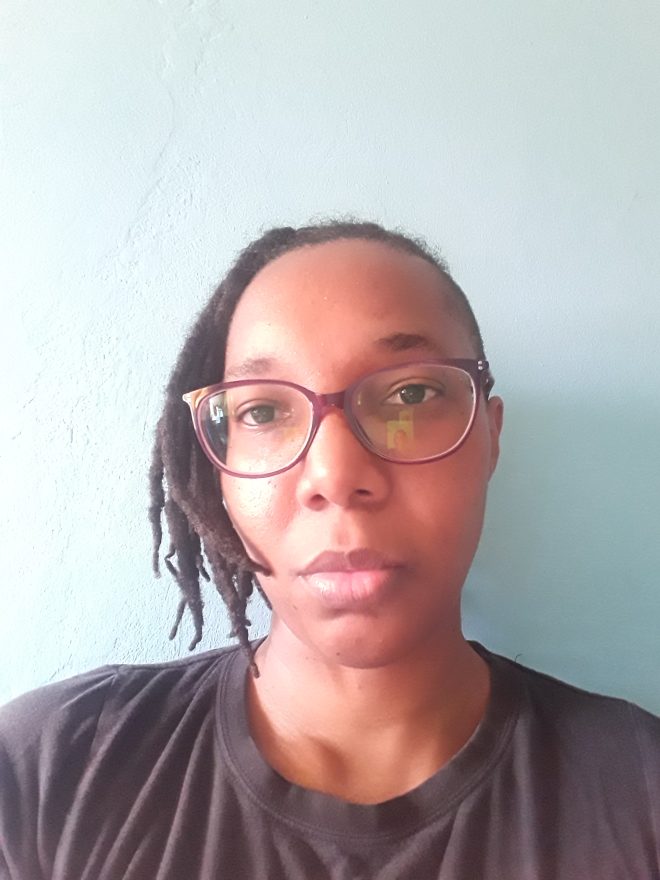

About the Narrator

Omega Francis

Omega Francis is a writer from Trinidad and Tobago and is a holder of a Bachelor’s degree in Communication Studies, and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus. Omega works as a copy-editor, writer and blogger and her writing has been published or is forthcoming in Harness Magazine, Outlish Magazine, SPED, UWI Today, UWI STAN magazine and Intersect.anu.