PodCastle 857: Ecdysis

Show Notes

Rated R

Ecdysis

by Samir Sirk Morató

My husband never got over being a lindworm.

Understandably. For over two decades, he was a serpent wider than an oak barrel and longer than a warship; for under two years, he’s been human. Had someone changed me from a shark-swallowing, black-and-blood-banded titan to a naked, knobbly beast with limbs, I would’ve killed them and myself, even if we were wed.

Yet wed we were. Our betrothal was as crushing as my husband’s past coils: because he was a princess-eating monster, he needed to be murdered; because he was a princely man, he needed to be married.

“My eldest needs a bride or a coffin,” the queen told my father. “He’s forbidding his younger brother from marrying before he does, and no more princesses will come. We’re out of options. Surrender your daughter.”

Sedition meant death for us both. So I arrived at the castle a condemned shepherd and left for my honeymoon a terrible bride-knight, blessed both with a wedding gown and a blade. Even then, I knew my blade was useless. Steel was nothing to a serpent’s scales. The younger prince’s broken sword had proved that. I entered my marital sea cave armed with nothing but vision.

Don’t ask me how I knew to wear ten shifts, or how to make my husband skin himself. Don’t ask about the way I whipped his muscle raw with lye-dipped whips, or bathed his agonized, slimy mass in milk, or how I fell asleep wrapped in his wet, warm coils, half conscious as they contorted and tore into a human form. Although that night ruined me, I live with the knowledge I enjoyed it.

So does my husband.

Despite the lack of choices, my once-worm chose peace. He no longer flounders while walking, or counts his vertebrae in bewilderment, or beds me in the tub. The lye I scalded him with now cleans our clothes, my ten shifts included; the whip lives in our bedroom. We’ve entered another era. Still, after dinner, I catch him hunched in the kitchen, wolfing raw herring scraps. He starts. I glimpse an old instinct in his delayed blink. My husband lacks the translucent eyelids he used to have.

“That will make you sick,” I tell him. I wipe a scale from his cheek.

He cradles my salt-stung hands in his. Flies walk across nearby potato peels and unwashed dishes from last night’s gathering. Outside, snow crusts the mountains’ gutters in sea snake stripes.

“I know,” he says. “I can’t help it.”

His tongue flicks out. Our fingers twine. My appetite quickens. Sweat creeps beneath my clothes. Every day, I better understand how my husband swallowed girls whole. How the queen ate two enchanted tulips to fill her womb without heeding the warning to take just one. Emptiness breeds hunger. I could devour three princesses yet starve for satisfaction; I’d eat a cursed bouquet without blinking.

I kiss a shred of meat from my husband’s mouth. It’s slick and cold. I don’t care for it. I just want to understand those flashes of wildness stripped from him yet never permitted to me.

“That will make you sick.” My husband’s nose scrunches. “Why eat it? You don’t crave raw fish.”

“I could. Maybe I’m pregnant. You don’t know.”

“You aren’t. I haven’t given you a baby because we don’t know if it’ll be a child or a worm. Or worse: twins.”

“You almost said egg, didn’t you?”

“Fuck you!”

Despite myself I laugh.

“No. That’s your job,” I say. “You’re braver than a soldier for doing your terrible duty daily and thoroughly. A martyr.”

My husband huffs. He thumbs my knuckles. My father and I are his family’s only in-laws with callouses. “I’d be less reliable if we had a child. Could you imagine even trying to cook if we had a wretched little worm threatening to swallow our fowl and wriggle out of her manners lessons?”

My throat closes because I have. Yet I’ve never managed to envision our baby. Not beyond fleeting, changing silhouettes. Ones that squirm. Our candles gutter.

“Do you really believe we’d make a lindworm?” I murmur.

“It seems possible. I was one even before I entered the world.”

The mountains dim into murky, vast shapes.

“I’d love our beast,” I say. “Our baby. Even if you couldn’t at first.”

“No. I would too. I already do. I just fear that if you birthed a worm, my family might never visit us again.”

“I’d prefer that.”

Our arranged marriage left my husband unarmed, me unheard, yet his kin adore mine. They’ve fattened my father with gifts. I’m glad for that — it’s the least they can do. My in-laws falter when it comes to adoring us. Whenever my husband and I aren’t wearing fineries never meant to fit, his mother can’t stand us. I’m unsure what she expected. Did she think I’d domesticate her son? My brother-in-law meets my husband and me where we are, but I can’t call dutiful acknowledgement love.

My husband guiltily embraces me.

Our second wedding told me all I needed to know about the royal family.

No subjects, my father included, saw the cracks in everything. They were busy celebrating. The feast-laden tables and sea of fancy robes didn’t distract me. Nor did the agony of an unexpected body. My husband’s twin, the younger prince, gawked at him when his newly forged hands could grasp neither wine glass nor fork at his own banquet. Everyone laughed, half charmed, half uneasy, when my husband gulped unchewed chunks of meat off his plate. My husband barely knew his own name — yesterday, his mother had chosen it for him. The queen, in her anxiety, had forgotten that she’d never christened her eldest son.

After sunset, my husband collapsed. He could no longer walk. “There are knives in my tail!” he repeated, clawing at his feet, writhing on the floor. His cries echoed through the halls. I’d only heard such pain from lambs being eaten alive. Guards carried him to his chambers before many peasants could see his seizing. The queen looked away, smile wobbling, and pretended all was well.

My husband’s twin downed a tankard of mead.

After everyone left, my brother-in-law and I lingered on a balcony, surrounded by celebratory scraps. No one else approached me. I wasn’t sure how to handle my husband; the servants weren’t sure how to handle me.

The younger prince and I watched stars scale the heavens.

“What a horrible thing we’re united in,” he said.

“I don’t follow.”

The prince pointed at a ragged slash on his cheek, pink with new skin. Then he pointed at the raw scrapes on my neck. No amount of courtly robes hid the way they climbed my throat.

“We both tried to kill him,” he said. “Neither of us asked for him. Now look. We’re responsible for trying to love him. We’ll be so for the rest of our lives.”

The prince spoke with bitter resignation. Although he was younger than his brother by minutes, and they shared the same lips and brow, he looked younger by years. Little age that came from hardship, duty, or loss marked his face, but its dark circles were starting to set in. My anger and isolation rose so sharply I almost retched.

Everyone else was just now accepting the unfair reality I’d learned as a girl.

Despite the biting air outside, our cottage is still hot from cooking. We stand sweating in our cluttered house, our belongings barely squeezed between all our gifts. After our in-laws’ visit, there’s even less space. I’m sometimes uncertain that either of us lives here.

My husband slips his hands beneath my apron. “Shed that layer.”

“All right, Prince.”

My husband rolls his eyes. “I’m trying to help you!”

His obscene flexibility doesn’t grant him the dexterity for undoing knots. I only tie bows now. I squirm back into my husband’s arms as he folds the apron. Despite myself, I relish it. Things learned are sweeter than those inborn. I held him skinned; I can sure as hell hold him now.

My husband sighs. “I liked myself better before.”

His hissed exhale burns me.

“You were dangerous,” I say.

“I knew myself.”

My longing to empathize vanishes. He’d loathe me for it. Whatever I am, it’s nothing like what he was. I wept before wedding him. All my night terrors about milky, churning coils come from my husband, even if he always holds me during and after. At first, his presence worsened them. I hated him for that. Then I hated myself for wanting him close.

It’s part of us now.

“You’ve come a long way,” I say.

Hatred still poisons my husband’s view of his body, regardless of how I love it for loving me. Is that selfishness? His mother sees the lindworm as a banished curse. In truth, she cursed me with banishing it. Why is others’ discontentment or destruction my problem? If I heeded the whisper that told me violence could solve it all, my life might be better. It’d probably be much worse. I lean into my husband to ground myself.

He points at the fish scraps.

“That herring came a long way too,” he says, using the voice he does when he knows I need distraction.

“Tell me about it.”

He does.

Twelve months into our marriage, my husband admitted that he’d always had a name. We were shoveling sheep shit into rye fields, then, one of many unroyal errands.

“Mother couldn’t say it. She also assumed I was nameless,” my husband said after I spluttered in fury. “When you see a snake, do you think they have a name? Do you think the rabbits you gut have titles?”

“No,” I told him. “But you’re no rabbit. You can speak. You’re her son.”

“And I’m fortunate she tolerates me, then doubly fortunate she loves me.” My husband cast another shovel of manure. “My mother appointed you to murder or marry me. Are you her knight?”

Tundra swans flew overhead. Their honking broke the storm clouds above them and raked the fallow fields beneath. Red clover tickled our heels.

“Only in words,” I said. “Maybe a little beyond that.”

My husband, who couldn’t smile then, pulled his lips taut over his teeth.

“What’s your name?” My blistered hands ached. So did my chest. “Your real name.”

“You won’t be able to say it either.”

“I don’t care. Tell me.”

When sea snake sounds rolled through his human tongue, I couldn’t comprehend them. “Repeat it,” I said, “but slower,” and for the rest of our shit shoveling, we went in circles, my husband resurrecting his lost name, me butchering it in different ways.

“You don’t have to learn it.” After my twentieth try, my husband dropped his shovel. His hair stuck in sweaty curls to his brow. His limbs shook. “My new name is fine.”

A memory of helpless concession crept into my head. Of mortality and wedding robes. It burned me. I hurled my final shovelful of dung as hard as possible. It scattered across serpent after serpent of tilled soil.

“I’m going to.” I scowled. “It’s your name. Until I get it right, I’ll just call you my husband.”

“My family will think you’re losing your mind.”

“I don’t care.”

I gathered both shovels. My husband stared at me in bewilderment. The white scars that marked where scales used to attach, a mesh that dappled his whole body, glowed beneath the dirt on his arms. He looked at me as if he were a creature from a dark world seeing sunlight for the first time. Uncertainty undercut me. Was this my selfishness masquerading as consideration?

“We don’t have to commit to this.” I shuffled, conscious of my dirty face and wide shoulders. “Is it something you want?”

My husband opened his mouth. Closed it. His lips pulled back once, then twice, before wobbling and pressing shut. He wiped his eyes. Though I had seen him in far more carnal situations, the glint of moisture stunned me. I looked away. It was my fault he’d gained a form that could cry. Watching him do it seemed violating.

“Yes,” my husband said. “It is.”

Maybe herring have more interesting lives than people. Maybe their lives sound so interesting because my husband loves talking about the seas that surround us.

Either way, since I’ve asked, my once-worm tells me about empires of herring eating empires of plankton in glacier-carved coves before the world feasts on them and their fucking. He waxes about sea lions, saithe, orcas, and tuna plunging through millions of herring, and seabirds piercing the surf like arrows to savage what they don’t take. Everything hinges on passion. Flesh. While my father and I ate herring for a year straight to avoid starvation, my husband swam miles undersea, biting his way through a world silvered with vicious vitality.

“Sometimes I forget that you’re too practical for cruelty,” I tell him. “Even if you’re petty.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

He hums into my hair. I brace my cheek against his collar.

“When you killed your first two brides and tried to kill me,” I say, “you were more hungry than you were vengeful. Everything in the sea has a name and voice, doesn’t it? Including those herrings. Everyone rips them apart anyway. When you came ashore, I bet people seemed no different than sharks or saithe. You didn’t realize that eating them made you a monster.”

“I expected a lindworm bride,” my husband confesses. “I didn’t know why the creatures who’d lent me their surname kept bringing me women like themselves. I assumed they were dowries. I’m grateful you survived. I wouldn’t have known what I’d lost by eating you.”

What did my husband lose when he ate the princesses besides more wealth? I imagine the two women in their wedding gowns, lush with braids and floral veils. I’m sure they flinched when they stepped into the bridal cave. Their feet hadn’t touched anything harsher than silk slippers or rushes. They couldn’t have whipped a lindworm. I bet they couldn’t even have milked a goat. Had I been the worm receiving brides, I would’ve squeezed them in half for living so softly while the rest of us suffered.

My husband, lost in thought, squirms. “After everything . . .”

I know what’s coming.

“Even while you were a lindworm, I skinned you. I beat you so hard you changed shape.” I cup his face. “You weren’t that big or bad. I’m not afraid of you anymore.”

My husband caresses the claw scar on my neck.

In some ways, I died when the queen enlisted me. My father and I grieved my death before I even left home. Wanting to live doesn’t overwrite knowing you won’t. Unlike everyone else, I was expendable. Dead princesses are expensive. So are dead knights. Dead shepherds are cheap.

Yet here I am.

I’ll never tell my husband what the queen requested last night.

My husband and I had been married for nineteen months. Because happiness had split our nightmares, and grudges had ebbed, we’d invited our families over to celebrate. The ale and chatter were thick when the queen towed me outside at nightfall. White-faced owls called in the wood.

“From one woman to another,” she said, mortified, “I’m sorry. God! I didn’t realize you were dressing him thrice a week. I can have servants sent out to do this for you.”

“That’s all right. It isn’t difficult.”

It wasn’t. I didn’t want people in my home anyway. Not in my business or under my power. I decided against telling the queen that for the first six months of marriage, I had dressed her son daily. She gave me a long look before taking my shoulders.

“I know you intended on being a common wife,” she said. “Not a monster slayer. Not a caretaker. Despite everything, you’ve cared so well for my eldest. Please, continue bearing him. We’ll provide whatever comforts make it easier.”

I stared. Her palms were soft. The fur trimming her sleeves cost more than my childhood cottage. My husband’s sibilant voice poured from the windows alongside the firelight.

“Bear him?” I said.

As if her son failed to function by choice. As if I didn’t catch him crushing laces between fingers he’d never asked for every morning and weeping silent, enraged tears when he couldn’t tie them; as if he wasn’t the first to see me in full, spit in my mouth, and call me worthwhile. The queen’s face twisted. She made the expression ewes did before abandoning malformed lambs.

“He should resemble his twin more,” she said.

“No one emerges from curses the way they were before,” I said, finally.

If I was tolerating my husband like some nursemaid then the tolerance was mutual. Maybe if he was a monstrous, tiresome ward, and I a common, tired wife, we would be tolerating each other.

I opened my mouth to tell the queen that I loved having her son inside my house. Inside me. I closed it when her ringless hands flashed in the dark. I had married her son on her order. We were chained together. She pitied us. If I confided in her, she’d look at me with discomfort. Our shared greed meant nothing.

The queen sniffled.

“Don’t fret.” I patted her arm.

“When I see my eldest now, I wish his scales had been soft,” she said. “Death would’ve been merciful. I love him too much to see the crippled way he lives. Visiting you is difficult for me.”

The queen looked at me as if I sympathized.

“Can you be a knight for me once more?” Her voice was low. “Can you finish this?”

I didn’t reply. When thoughts about biting chunks from her face wormed in, I withdrew my hand. We returned inside.

As my husband argued with the twin he didn’t mirror, something close to affection in their voices, I drank. I convinced myself that the exchange outside had never happened. Reality assaulted me again when I sat in my husband’s lap and teased him about the difficulties of strangling geese for dinner. While my father and brother-in-law laughed, I glimpsed the queen’s face. Her disgusted confusion stunned me.

Then I understood: to her, my husband remained a burden, and I remained a poor, brave commoner who should’ve been a shepherd’s wife, and things like us did not desire, or ponder shed skins or knighthood or bodies made by mistake, or voice filthy truths about being alive.

The queen couldn’t comprehend me loving her son in a way cruder than a pastoral portrait, if at all.

I won’t forget the horrors my husband and I have inflicted on each other, but I trust his gentleness now. I trust the worm who carries me, on my worst days, the way I first carried him. It’s not enough for the one who made him. It’s enough for me.

“We should go sailing,” I murmur. “Show me your home.”

I should’ve unsloughed my shifts and become a beast instead. What a wedding that would’ve been. My husband trembles.

“It isn’t the same,” he says. “It will never be the same.”

“It never is.”

How ironic: we’re both worms turned unwilling heroes. My husband sobs. We embrace, terrestrial and terribly alive, left to all our rituals that are supposed to make life run. When we’re finished crying, I kiss him hard enough to catch my lip on his teeth.

“I want a baby.” My bleeding mouth mashes against his. “I want twins. I hope they’re worms. I hope they eat this fucking miserable kingdom. No one expects us to be happy or alive. We’ll be both.”

My husband licks the blood from my lip. He may love his family, but the way his hands shiver over me tells me that he loves me more. Me, with all my cruelty, hunger, and determination to live. He grabs a fistful of my hair and bites at my ear.

“I hope they’re worms too,” he whispers.

Before I fuck my husband, I think: The queen would find me monstrous. That isn’t new. If the queen knew that her son and I had coupled mere hours after his transformation to grieve what we’d lost at outside whims — to grieve with the other person we had robbed — she would’ve looked at me like I was a lindworm.

God forbid she finds out I told my husband that I could love him as a worm too, if he’d take me. She’d be horrified.

She might even order some other poor girl to kill us.

Host Commentary

..aaaaand welcome back. That was “Ecdysis” by Samir Sirk Morató, and if you enjoyed that—adored that, felt that—then happily there’s plenty linked from their website, spicycloaca.wixsite.com

I don’t even know where to start with this one. It is too big, too important to me to broach. Ableism is… okay, so this will get messy (and, fair warning, sweary) because it will get personal, and a lot of what this story has stirred up for me is shit I haven’t yet resolved in my own head, so please forgive me both the rambling and the inevitable missteps in what I’m about to say: I am imperfect, and I am struggling towards comprehension and resolution. Ableism is embedded deep inside me, was put there by the flawed society I grew up and continue to exist in, and I am fighting so hard to overcome it because the primary person I hurt with my ableism is myself.

For a lot of years I put a huge amount of pressure on myself to push through, keep going, take on everyone’s burdens and get on without complaint and achieve, because what did I have to complain about? I was white, male, cis-hetero and middle-class and able-bodied, from a comfortable country that has forgotten what conflict actually feels like. This, as I’ve spoken about at length, was not entirely true in hindsight, and resulted in a massive mental collapse through 2021 as the burnout of unconsciously compensating for undiagnosed neurodivergence finally scorched through the last of my reserves and left me a barely-functioning, deeply unpleasant shell of a person. The work to rebuild from that has been long; is on-going; and will still fall short of who and what I was capable of before.

I am, undoubtedly, disadvantaged and overburdened by my neurological differences. Autism and ADHD are not superpowers, despite what some well-meaning but ultimately very-irritating people insist. For the most part they are just differences, and certainly for me a large part of my struggles are grounded in the social model of disability, wherein issues only arise because the world isn’t set up to accommodate me; please, do look that phrase up to read more. But there is still a portion of both diagnoses—and always some portion, greater or lesser for those of us across the spectrum—that is, bluntly, a disability.

And as I write that, it occurs to me: why did I need the adverb “bluntly”? And the honest answer is because “disability” feels like a value judgement; feels like a curse, an invective. This is internalized ableism. This is ugly and wrong and repairing it is the work I am trying to do, and I am frightened to be so honest about this flaw in myself here. But it illustrates exactly the point I need to make, the point that sang in the bones of this story and gave me both goosebumps and tears: disability is not a dirty word. I shouldn’t shy away from it! Fuck, I shouldn’t even embrace it, because it simply should not be that important!

It’s not just me that’s disabled in our household. We’re all diagnosed with one or more flavours of neurodivergence now, but my wife Claire was also diagnosed with multiple sclerosis 3 years ago, and we are still coming to terms with that, and it’s still continuing to take its degenerative toll. We were at WorldCon together a few weeks back, in Glasgow, and there was much discussion beforehand about her taking her mobility scooter: she can walk, but the fundamental debility of her MS is energy levels, and walking for an hour will wipe her out for the rest of the day and exacerbate all the other symptoms—the balance, the grip strength, the ability to find words, all the myriad fucked up ways that that disease steals from you. It should not have been a debate… but for the internalised ableism, the fear of society seeing you differently, the anxiety of standing out.

And here’s a thing we’ve noticed since she’s used a mobility scooter, a really fucking upsetting thing, and something that I admit I am a lesser person for not fully recognising before it affected us personally: once you are disabled, you are invisible, because people would rather pretend you didn’t exist. Some of it, I think, is misplaced politeness: fear that acknowledging the difference would be so rude that it is better to not even acknowledge the person at all, which is eighteen shades of fucked up and wrong. Some of it, though, is just plain ableism, I’m sure: that animal fear of disability, disease, difference; the pity, oh my gods the disgusting pity.

And so when the Queen, here, asks the wife to bear her husband, like a fucking cross she must drag to Golgotha; when she says “Death would’ve been more merciful. I love him too much to see the crippled way he lives” as if there could not possibly be any joy in his life, still, because she cannot imagine such if she shared the same burden; when the wife recognises that the queen “couldn’t comprehend me loving her son”: holy shit do I feel seen in a way that I still struggle to see myself.

And talking of “Death would’ve been more merciful”? That’s the true sentiment underlying anti-vaxxing, the one they’re too ashamed to state plainly: “I would rather risk my child’s death than risk them being autistic like yours.” Fuck you. Fuck you.

Ableism not only taints the way the world treats disabled people: it is so omnipresent that it soaks through your skin and taints the way disabled people treat themselves. It is oppressive and inescapable and so completely, utterly, fucked.

Claire and I were each only diagnosed as autistic last year, halfway through our lives. So when we met, we were not only mistaken about ourselves being neurotypical, we were mistaken about the other being neurotypical. We have spent our marriage unconsciously translating from autistic to NT for the sake of the other person, who then had to translate back from NT to autistic anyway, and so we were mistakenly putting layers between us when we could have just connected directly. But we know, now. We are working to understand what our own needs actually are, and how to express them to the other; we are learning communication strategies that work for us, not for a world where politeness and approaching topics side-on matters more than clarity. I hope, and trust and believe and crave, that we make it, that we build to a new understanding of ourselves and each other; and like the wife and the worm here, returning to his home, it won’t be the same, it will never be the same; but it will be us, it will be ours, and fuck anyone who thinks it’s wrong for that.

So thank you, Mx Morató, for this story, this incredible story. I hope it changes the world, and I hope everyone who’s listened to it today goes away and thinks about the ableism they too have internalised—and I honestly say that without rancour and without judgement, because you cannot be blamed for what you have unconsciously inherited, only for what you do or do not do once you recognise it’s there. But at the very least, this story is changing my world, and changing me. Thank you. Thank you.

About the Author

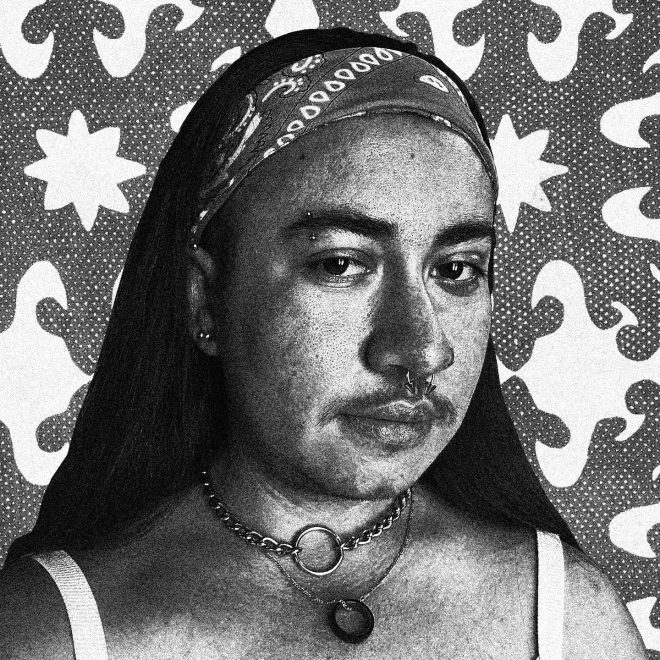

Samir Sirk Morató

Samir Sirk Morató is a scientist, artist, and flesh heap. They are also a two-time Brave New Weird shortlister and a F(r)iction Fall 2022 Flash Fiction finalist. Some of their published and forthcoming work can be found in The Skull & Laurel, Flash Fiction Online, ergot., NIGHTMARE, and The Drabblecast.

About the Narrator